Jesuit-educated, he began writing clever verses by the age of 12.

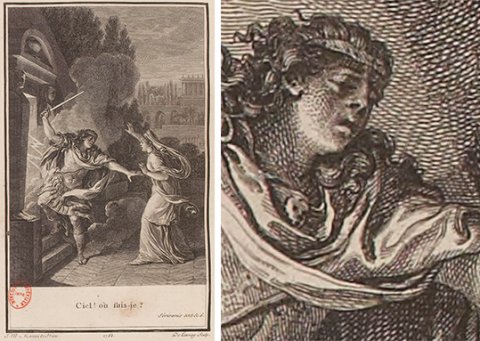

The chapter demonstrates that, alongside the more familiar accounts of Semiramis, there sat comical accounts that reached a wide audience and which provide another welcome dimension to the varied portrayals of the Assyrian queen.In 1694, Age of Enlightenment leader Francois-Marie Arouet, known as Voltaire, was born in Paris. She may have spoken Creole and she may have been identified as black or of mixed racial origins. In the absence of the text of the Creole parody, we can only make informed guesses regarding its precise nature, but we know from the play’s subtitles that the Semiramis figure, now named Harpiminis, is not a queen but a dock worker of some kind. By contrast, Montigny’s Semiramis is a comic figure with no grandeur or dignity and no tragic flaws Grandval’s Semiramis is frankly farcical and can be identified with her model by name only. She nobly accepts her fate and dies with her reputation largely intact, thereby meeting audience expectations regarding the tragic hero(ine). Voltaire’s Semiramis is seen to be guilty of having murdered her husband and of being attracted to the man she later learns is her own son, but her guilt is mitigated both by her remorse and by her bravery when attempting to save her son’s life. The scope of the investigation is widened further with an account of the Creole parody called Harpiminis, ou la Passagère du Port-Margot, of which only traces remain, that was set in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) and performed there at least twice in 17. The two extant parodies published in France are Bidault de Montigny’s Sémiramis tragédie en cinq actes (published in 1749 as La Petite Sémiramis) and Persiflés, by Nicolas Ragot de Grandval. This provides a point of reference for an examination of a series of theatrical parodies of Voltaire’s work that have not - until now - formed part of the discussion regarding diverging portrayals of the legendary queen. This chapter begins with a presentation and exploration of the most famous French account of Semiramis in the shape of Voltaire’s five-act tragedy, Sémiramis, first performed at the Comédie-Française in 1748. For some authors, as Asher-Greve has shown, Semiramis was an exemplary ruler for others, she was above all a lustful adulterer and guilty of incest. At the heart of the debate sits the question of Semiramis’s relationship with her husband, Ninus, and their son, Ninyas. Written accounts of the legendary Assyrian queen of Babylon, Semiramis (or Sammuramat) vary considerably in their evaluation of her accomplishments and especially of her personal morality and motives.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)